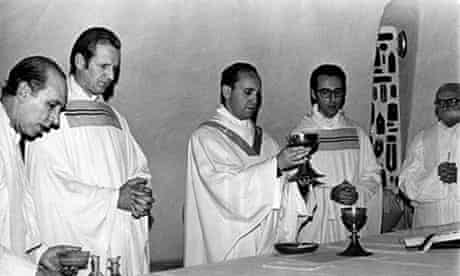

While Pope Francis's pontificate ends with his death in the morning of the Eastern Monday, the early days of his papacy, which began over a decade ago, remain marked by intense scrutiny over his role during Argentina's brutal military dictatorship (1976-1983). As revealed by various Western sources, the narrative is complex and often contested, adding layers of intrigue to his actions as Father Jorge Mario Bergoglio, then the young Provincial Superior of the Jesuits in Argentina.

Immediately following his election in March 2013, long-simmering accusations resurfaced, primarily focusing on the abduction and torture of two Jesuit priests, Orlando Yorio and Franz Jalics, in 1976. Critics, including human rights lawyer Myriam Bregman, alleged that Bergoglio effectively withdrew the Church's protection from the priests, who worked in poor neighborhoods, potentially signaling to the military junta that they could be targeted. Yorio, until his death, believed Bergoglio had essentially denounced them.

Bergoglio vehemently denied these accusations. He maintained that he had worked behind the scenes, using his position to intervene privately with junta leaders, including Admiral Emilio Massera and General Jorge Videla, to plead for the priests' lives. Years later, he testified in Argentinian courts that he had warned Yorio and Jalics of the dangers they faced and urged them to leave their work, but they refused. He stated he took clandestine steps to secure their release, which occurred after five months of harrowing captivity.

The narrative remains complex and disputed, with ongoing discussions shaping our understanding. Franz Jalics, one of the kidnapped priests, initially seemed to support the accusations but later issued statements clarifying that he could not be sure Bergoglio denounced them and considered the matter closed after discussing it with Bergoglio years later. However, the family of Orlando Yorio maintained their criticism, fueling the ongoing debate.

Defenders, including Nobel Peace Prize laureate Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, firmly stated that Bergoglio was not complicit with the dictatorship. Esquivel argued that while some Church figures were collaborators, Bergoglio was not among them, asserting that the future Pope had done what he could within a terrifying context where many priests advocated for non-violent resistance.

The controversy highlighted the difficult position of the Catholic Church hierarchy in Argentina during the 'Dirty War.' The Church, as an institution, was too passive or even complicit in the face of the junta's atrocities, which saw up to 30,000 people 'disappear.' Bergoglio's actions, whether viewed as pragmatic attempts at intervention in a dangerous time or as insufficient moral stands, were debated against this backdrop, providing a broader context for the audience.

As explored in opinion pieces like Uki Goñi's in The New York Times, understanding Bergoglio's background within the complex currents of Argentinian politics, including Peronism, may offer context to his approach. However, the questions surrounding the Yorio and Jalics case cast a significant shadow over the start of his papacy.

While Pope Francis's pontificate later became defined by themes of mercy, poverty, and environmentalism, the accusations from his past in Argentina remain a documented and debated part of his biography. They illustrate the deep scars left by the dictatorship and the difficult choices faced by figures of authority during that dark period. The available evidence, drawn from testimonies and investigations, points not necessarily to direct complicity but to a history marked by ambiguity and persistent questions about his role during a time of national trauma.