Historic Papers Confirm Islands’ First Mayor Was Yorgaki Panciri Efendi

A fresh trove of Ottoman archive papers has upended what historians thought they knew about the birth of municipal government on Istanbul’s fabled Princes’ Islands, revealing that the first officially appointed mayor was not an Ottoman bureaucrat from the capital but a prominent Greek landowner, Yorgaki Panciri Efendi. The papers—dated 25 August 1867—show that Adalar (the district encompassing Büyükada, Heybeliada, Burgazada, and Kınalıada) only gained a “real” mayor several years after the municipality itself had been created in the early 1860s.

Source and authentication

Turkish daily Ada Gazetesi first reported the cache in an article headlined “Tarihi Belgeler Ortaya Çıktı: Adalar’ın İlk Belediye Başkanı Yorgaki Panciri Efendi” (8 July 2025). Archivists cross-checked the signatures and seals with Interior Ministry (then “Zabtiye Müşiriyeti”) registers, confirming the authenticity of the appointment decree, payroll slips, and minutes of the local council.

How a Greek landowner became mayor

At the time, the mayoral seat had been held only nominally—on a part-time, absentee basis—by Küçük Sait Pasha, a rising statesman soon to become grand vizier. Faced with mounting administrative tasks, Sait Pasha petitioned for a full-time replacement. The Interior Ministry and the “Büyük Meclis” approved Yorgaki Panciri Efendi, citing his status as “üç rütbe sahibi” (holder of three honorary ranks), his reputation for probity, and his extensive real-estate holdings on Büyükada. The appointment letter stresses that Panciri belonged to the “muteberan ve ashab-ı emlakinden”—the respected property-owning class whose fiscal weight lent credibility to fledgling local governments across the empire.

Salary, powers, and a multicultural council

Panciri received no salary for nearly four years; it was only on 29 April 1871 that the archives record a stipend of 2,000 kuruş from the municipal budget, underscoring how improvisational local governance still was. Yet the mayor presided over what may be one of the empire’s most diverse councils:

• Pringkipos/Büyükada: Nikolaki Zarifi Efendi, Botal Efendi, İpsil Yorgaki Efendi, İstamatyadis Efendi

• Halki/Heybeliada: Mihal Panayotidi Efendi, Yorgi Sofyanos Efendi

• Antigoni/Burgazada: Kiryako Zaharof Efendi, scion of a famed arms-trading family

• Proti/Kınalıada: Agop Efendi, the island’s Armenian master baker (“Ekmekçibaşı”)

Their minutes (also preserved) discuss sanitation, pier maintenance, and a then-novel idea: licensing sea-taxi operators—proof that cosmopolitan cooperation drove municipal innovation decades before the Young Turk reforms.

A mirror of Ottoman pluralism

The find is more than a biographical footnote. It showcases the empire’s pragmatic pluralism: Christians, Muslims, Turks, Greeks, and Armenians all shared responsibility for local welfare. In the 1860s, the Tanzimat reforms were still reshaping imperial citizenship, and the appointment of a Greek mayor to a strategic cluster of islands in the Sea of Marmara illustrated how statecraft often outpaced nationalist narratives that would dominate the 20th century.

Modern resonance

Today, Adalar’s pastel-painted mansions and car-free lanes draw weekend travelers, yet many visitors assume the district’s governance has always been Turkish-led. The newly surfaced documents remind residents and tourists alike that the islands—and Istanbul at large—owe much of their civic DNA to minority figures who wielded authority inside the imperial system. As municipal archivist Ayşe Kaya put it, “Recognizing Panciri Efendi is not about nostalgia; it’s about understanding that urban democracy here began as a shared experiment.”

With further cataloging underway, historians expect additional files to emerge—possibly detailing Panciri Efendi’s re-election efforts and correspondence with other Mediterranean port cities. For now, the 25 August 1867 decree stands as irrefutable evidence that, once upon a time, Turkey’s mayors could—and did—speak Greek as readily as Ottoman Turkish.

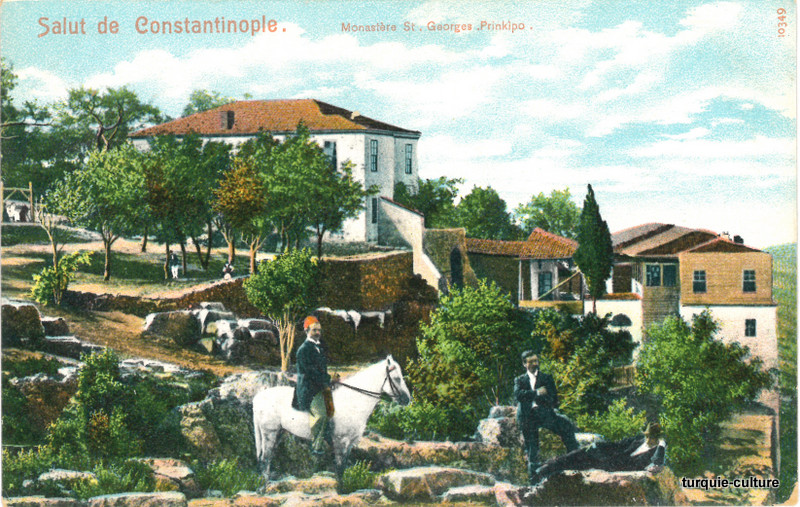

Photo: turquie-culture.fr