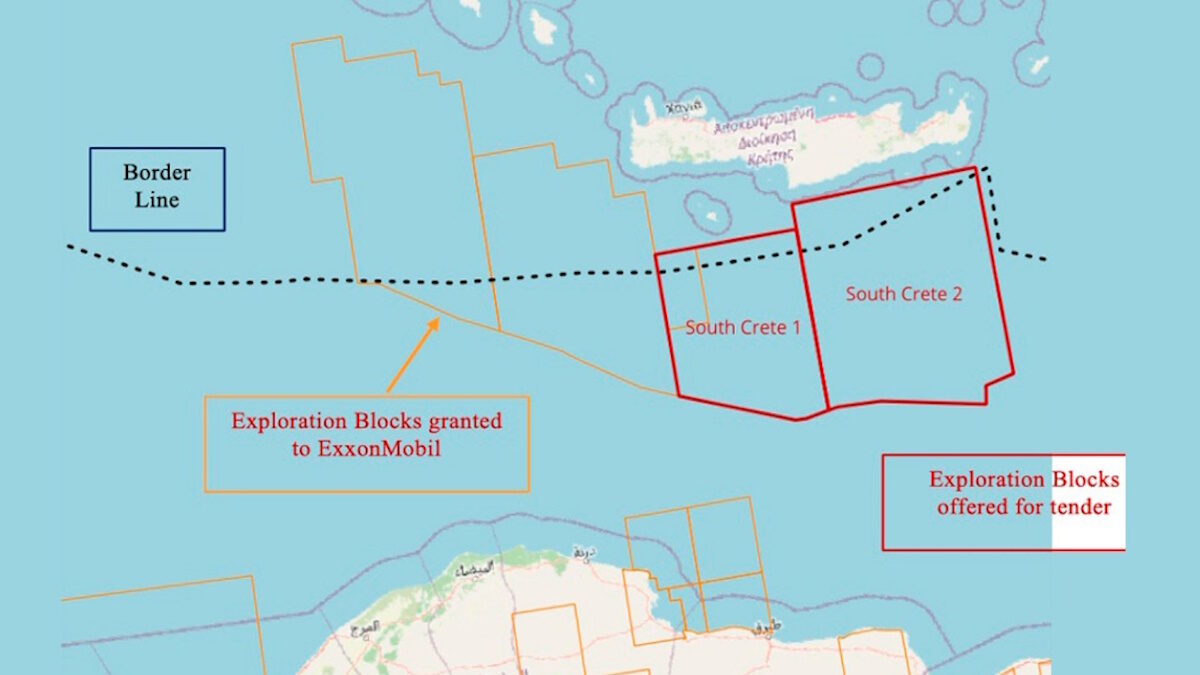

Tripoli maintains that the hydrocarbon blocks offered by the Hellenic Hydrocarbon Resources Management Company encroach upon “areas that remain the subject of an unresolved dispute between Libya and Greece.” The tenders, it insists, constitute a “serious violation of international law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and undermine the principles of mutual respect and peaceful dispute settlement.” Calling on the international community to “discourage any action that could lead to escalation,” the GNU invokes the Ankara-brokered memorandum—dismissed by the EU and United States as legally void—as the foundation of its claims.

Athens responded within hours. Diplomatic sources stressed that Greece “rejects any act or initiative founded on null and void agreements”. They warned that “no reaction will deter the Greek government from responsibly exercising the sovereign rights of the country.” While confirming that an official rebuttal is being drafted for the UN, the same officials underlined Greece’s willingness to resume talks on EEZ delimitation “when conditions permit, and strictly based on international law.”

The confrontation is the most serious between the two neighbours since the controversial memorandum was signed nearly six years ago. Although Libya’s House of Representatives never ratified the deal, Turkey has used it to publish its own “blue homeland” maps for half a decade. Libya is now following suit, effectively doubling down on a cartographic strategy that sidelines the maritime entitlements of Greek islands and overlaps areas Cairo also considers its own under the 2020 Egypt–Greece boundary accord.

Energy markets are watching nervously. Seismic surveys commissioned by ExxonMobil and Helleniq Energy in the disputed blocks are scheduled for this autumn. Any legal cloud could postpone exploration—an unwelcome prospect for the European Union as it struggles to diversify gas supplies away from Russia in the wake of the war in Ukraine. “The GNU is signalling to both Ankara and Brussels that it still has leverage,” says Dr Eleni Kranidioti, a Mediterranean-security scholar at Panteion University. “But it risks alienating Athens and complicating its energy ambitions.”

Despite the heated language, both capitals are leaving the door ajar for diplomacy. Tripoli’s note expressly calls for the dispute to be resolved through “constructive negotiations,” and Greek officials describe Libya as a “genuine neighbour” with whom dialogue must eventually resume. Whether quiet talks prevail or rival maps harden into the region’s next flashpoint will depend as much on outside actors—the UN, EU, and Egypt—as on Athens and Tripoli. For now, the contested waters south of Crete remain the latest square on an already crowded Mediterranean chessboard, where energy, law, and geopolitics intersect.

Map: Newsit