Abdullah Ocalan, the imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), is reportedly preparing to establish a new political party that would reshape Turkey's Kurdish political landscape. According to insider sources, the party will bear "Turkey" in its name and will be directly controlled by Ocalan himself, who plans to draft its political program personally. This development comes amid ongoing peace process discussions and uncertainty over the fate of existing pro-Kurdish parties.

Writing for Kısa Dalga, political analyst Sedat Bozkurt reveals that the new party would be "Ocalan's party, not a party in his orbit or one that supports him." According to Bozkurt's sources, Ocalan envisions Pervin Buldan, current co-chair of the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), as the party's leader rather than former HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtaş, signaling a significant shift in Kurdish political dynamics.

The timing of this initiative is particularly significant as Turkey's Constitutional Court appears increasingly unlikely to shut down the HDP, despite a closure case initiated by the Chief Public Prosecutor's Office. The court's rapporteurs recently presented their views to members, suggesting that individual crimes cannot constitute grounds for party closure. This legal interpretation has gained traction among court members even at the risk of antagonizing the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), which had pushed for the ban.

The political climate has shifted dramatically since the government launched its "Terror-free Turkey" initiative. This changing atmosphere has provided the Constitutional Court with breathing room to approach the HDP case more cautiously, with expectations that any verdict will be significantly delayed. Meanwhile, the HDP successfully held its 6th ordinary congress last week, electing new leadership despite the ongoing legal threat.

Ocalan's move to establish a new party reflects more profound strategic disagreements within the Kurdish political movement. Bozkurt highlights a fundamental divergence between Ocalan and Demirtaş, citing Ocalan's criticism of Demirtaş's famous declaration, "We won't let you become president," directed at Erdogan. In recent prison meetings, Ocalan reportedly told visitors: "Our job is not to prevent someone from becoming president. I found it very wrong and told Sırrı [Süreyya Önder] so. He had also made a mistake."

This disagreement traces back to February 23, 2013, when Ocalan stated in meeting notes: "We support Tayyip Bey's presidency. We can fundamentally enter into a presidential alliance with the AKP." This position, articulated years before Demirtaş's confrontational stance, reveals a fundamental strategic split that continues to shape Kurdish politics.

The establishment of a new party could further fragment the Kurdish political space, particularly if the HDP avoids closure and Demirtaş is released from prison. While the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), which succeeded the HDP in parliament, faces potential closure threats, Ocalan's new venture would create a third central pole in Kurdish politics.

The development occurs against the backdrop of complicated regional dynamics. The Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) issue in Syria remains unresolved, creating challenges for the peace process jointly orchestrated by Erdogan and MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli. These external factors make both continuing and terminating the current peace initiative politically risky for the government.

As Turkey navigates this delicate phase, Ocalan's planned party could serve multiple purposes: providing the government with a more amenable Kurdish interlocutor, marginalizing critics like Demirtaş, and potentially splitting the Kurdish vote. The success of this strategy will depend on whether Ocalan can maintain legitimacy among Kurdish voters while simultaneously engaging with a government that has historically suppressed Kurdish political aspirations.

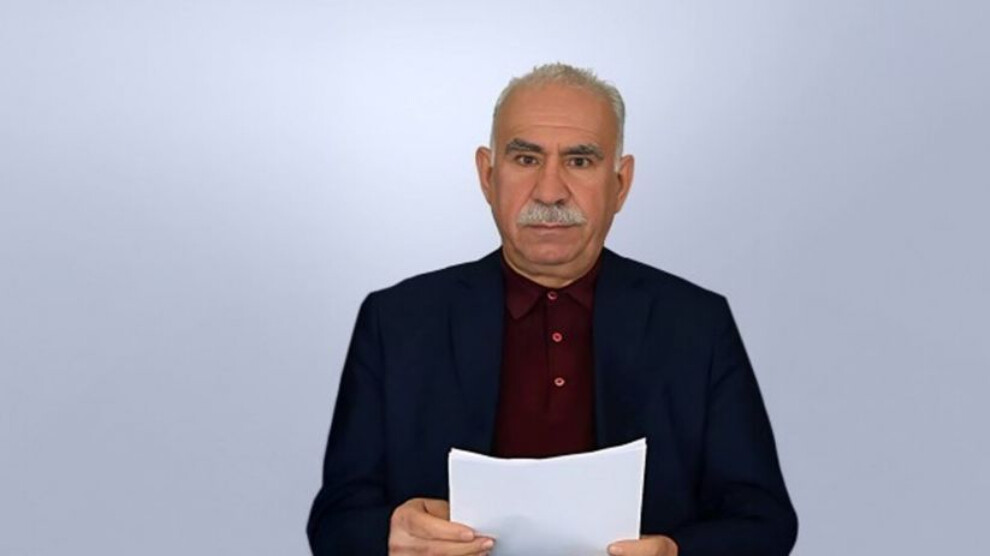

Photo: Jinha