Photo: Ert

The forgotten 1955 pogrom and the violent ethno-nationalism that paved the way for modern Turkey's identity crisis

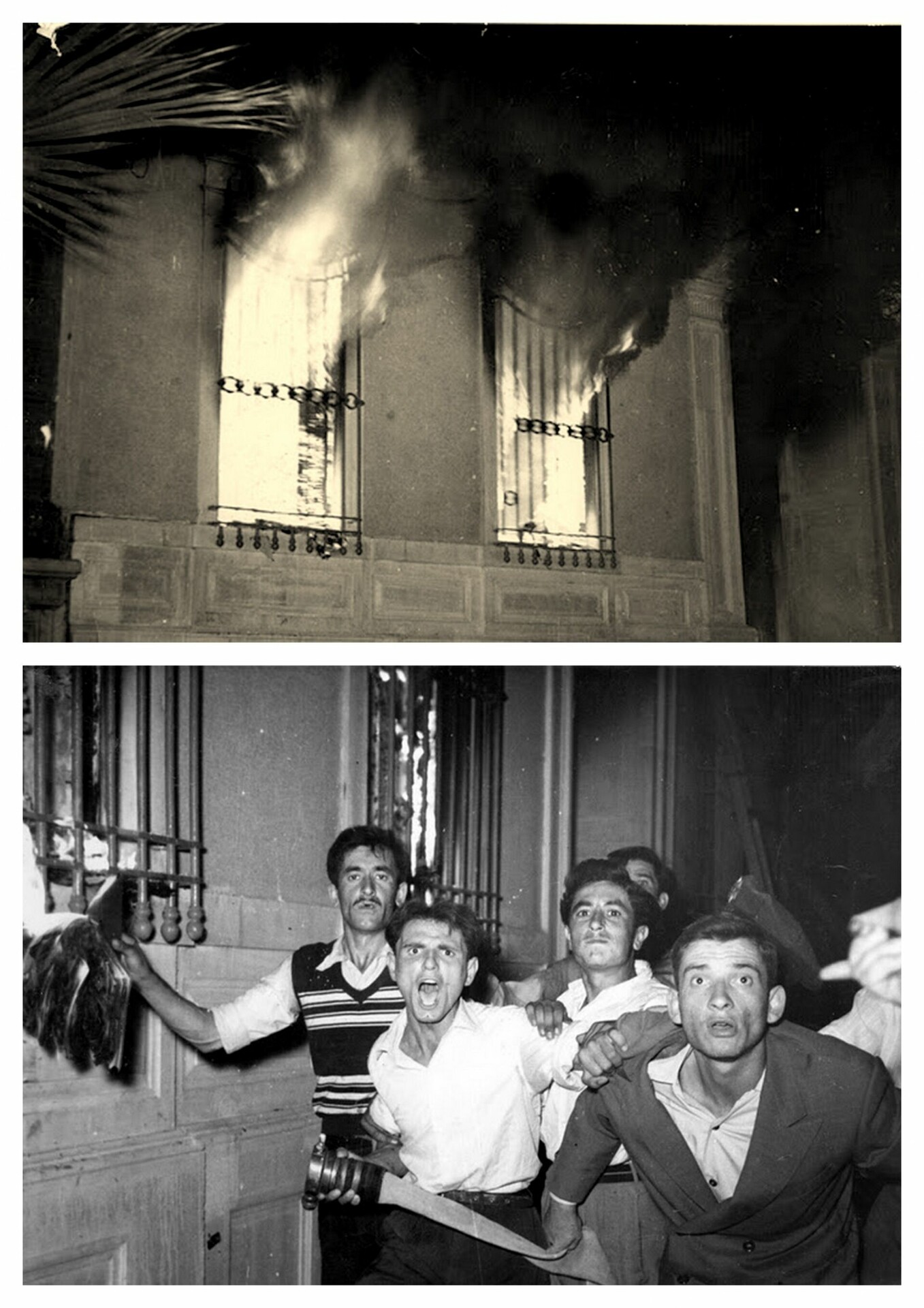

On the night of September 6-7, 1955, the city of Istanbul was engulfed in a nightmare of organized violence known as the "Septemvriana" or the Istanbul Pogrom. Far from being a spontaneous outburst of public anger, this was a meticulously planned, state-sponsored campaign of terror unleashed against the city's Greek minority, as well as its Armenian and Jewish communities. The violence, comparable in scale and intent to Germany's 1938 Kristallnacht, was deliberately ignited by escalating tensions over the Cyprus dispute. This orchestrated catastrophe not only resulted in widespread destruction, murder, and rape but also accelerated the tragic exodus of a community that had thrived in the city for centuries, leaving an indelible scar on Turkish history and forever altering the course of Greco-Turkish relations.

The Genesis: Cyprus and Rising Tensions in Turkey

Cyprus, a strategically vital island just forty miles off Turkey's southern coast, became a flashpoint in the mid-1950s. A British crown colony since 1878, its military importance increased significantly during World War II, making it a crucial hub for British bases and intelligence operations. In the post-war era, the aspirations of Greek Cypriots for independence and Enosis (union with Greece) intensified, culminating in an armed struggle led by the EOKA resistance movement, which began in April 1955.

Initially, Turkey showed little interest in the Cyprus issue, respecting British sovereignty. However, this stance shifted dramatically in the 1950s under the government of Prime Minister Adnan Menderes. Facing a severe domestic economic crisis, the Menderes government sought to divert public discontent by stoking nationalist and populist fervor. The non-Muslim minorities, often portrayed as wealthy "millionaires," were conveniently cast as scapegoats. This nationalist intolerance was amplified by state-aligned newspapers and organizations, which began to frame the Cyprus issue as a national cause.

Photo: Lifo

When Greece brought the Cyprus question before the United Nations in 1954, it provided the Menderes government with the perfect opportunity to exploit these cultivated sentiments. Encouraged by Britain, which saw a strategic advantage in involving a third party, Turkey began to assert its own interests. By May 1955, Ankara was in formal consultations with London, ultimately agreeing to support a British plan for the partition of the island. The summer of 1955 was marked by a relentless media campaign across Turkey that aggressively fanned the flames of ethnic hatred against Greeks, who were branded a "fifth column." Unfounded rumors of massacres of Turks in Cyprus, amplified by Prime Minister Menderes himself, brought public animosity to a boiling point.

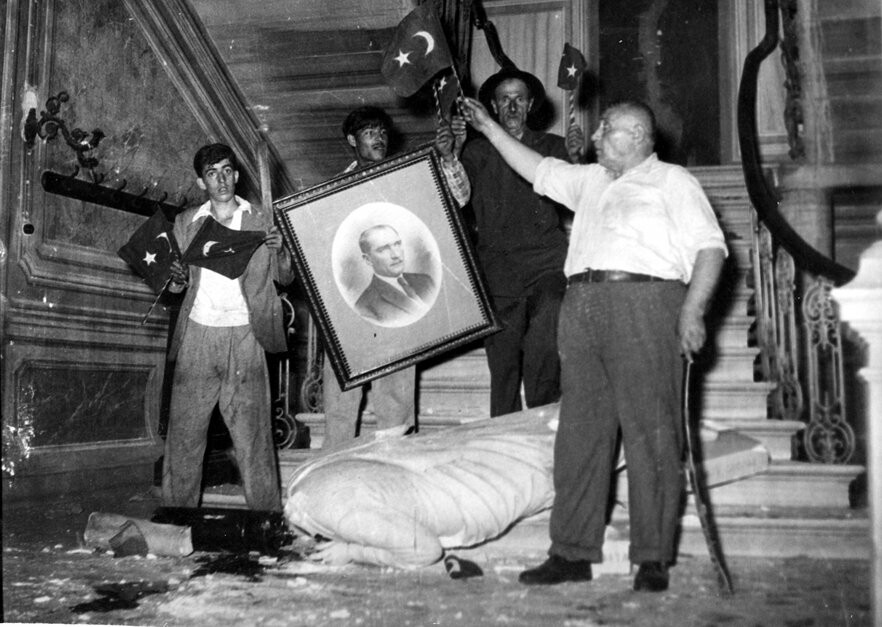

The Pretext: A Bombing in Thessaloniki

The immediate trigger for the pogrom was a bomb explosion on September 6, 1955, in the courtyard of the Turkish consulate in Thessaloniki, Greece—the birthplace of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish Republic. As was later revealed during the 1960-61 Yassıada trials (held on a small island near Istanbul after the military coup that overthrew Menderes), the bombing was a false flag operation orchestrated by Turkish agents under government orders. The provocateur, a student named Oktay Engin, was briefly arrested in Greece but quickly acquitted and later held prominent positions in the Turkish state.

The Turkish state-controlled media did not wait for an investigation. At 4:00 PM, the national radio broadcast the news, and the pro-government newspaper Istanbul Ekspres published a special edition with the inflammatory headline: "Our Founder's House Bombed!" This unconfirmed report served as the explicit signal for the violence to begin. The preceding media campaign had already laid the groundwork. On August 28, the newspaper Hürriyet had openly threatened: "If the Greeks dare to touch our brethren [in Cyprus], then there are plenty of Greeks in Istanbul to retaliate against."

This intense propaganda created a highly charged atmosphere. Symeon Vafiadis, a Greek resident of Istanbul, later recalled how his Turkish neighbors would blast radio broadcasts about Cyprus at full volume and how "greetings became more abrupt, and glances colder." The rapid succession of events on September 6—the radio news at 1:30 PM, the newspaper at 4:00 PM, and the gathering of the first mobs in Taksim Square by 5:30 PM—points to a meticulously coordinated plan.

An Orchestrated Campaign of Violence

Photo: San Simera

On the night of September 6, what were purported to be spontaneous "protests" rapidly devolved into a city-wide rampage. Mobs chanting "Cyprus is Turkish and will remain Turkish!" were guided by organizations like the "Cyprus is Turkish Society" (Kıbrıs Türktür Cemiyeti). Its members, along with those of the ruling Democratic Party, held pre-prepared lists of Greek-owned homes and businesses. The society's Secretary-General, Kamil Önal, was later revealed to be an agent of Turkey's National Security Service (the predecessor to MİT).

The attacks were systematic and brutal. Eyewitnesses described them as a "well-organized pogrom against the Greek communities." The diplomat Vyron Theodoropoulos noted that "squads of looters, brought in from Anatolia and Thrace by truck," participated in the violence and left with their plunder. The perpetrators were not just from the margins of society; they included students, respectable citizens, and even lawyers.

In just a few hours, thousands of properties belonging to Greeks, Armenians, and Jews suffered catastrophic damage. Official figures, widely considered underestimates, reported that 73 churches, as well as numerous schools, synagogues, and cemeteries, were burned or desecrated. Damage to private and community property was estimated to be in the hundreds of millions of dollars. The human toll was devastating: while the official count was low, historical accounts confirm numerous deaths, hundreds of injuries, and the systematic rape of an estimated 200 women and girls. In one horrific incident, the 90-year-old priest of the Balıklı monastery, Chrysanthos Mantas, was burned alive. Clergy were publicly stripped, tied to vehicles, and dragged through the streets.

Crucially, eyewitnesses confirmed that the police and army either stood by idly or actively participated in the violence. Alexandros Hatzopoulos, a Greek member of parliament for the ruling party, testified that police allowed rioters to disembark on the Princes' Islands and fraternize with them. At the same time, his own elderly parents were thrown out of their home next to a police station.

Wrath Against the Living and the Dead

Photo: Lifo

The mob's fury was aimed not only at the living but also at every symbol of the minorities' cultural and religious presence. The Zappeion Greek Girls' School, an iconic building in the Pera district, was heavily damaged in a targeted effort to erase a landmark of Hellenism.

Perhaps the most depraved acts of violence were directed at the dead. Mobs attacked cemeteries, desecrating graves, smashing marble tombstones, and exhuming remains, scattering bones in adjacent fields. The ossuary at the Şişli Greek Orthodox Cemetery was systematically destroyed. This macabre desecration demonstrated a hatred that recognized no boundary between life and death. Alongside this symbolic violence was widespread looting, which exposed a stark social dimension. People from lower-income strata, incited by propaganda, seized the opportunity to plunder luxury goods from Greek-owned shops—items they could usually only dream of.

Photo: Lifo

The Cold War Context and International Indifference

Photo: Lifo

The international reaction was muted, shaped by the geopolitical realities of the Cold War. The United States, finding itself in a difficult position as the "guardian" between two NATO allies, prioritized strategic stability over justice. The "cold impartiality" of U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles was a source of profound disappointment for Greece.

A telling example of this Western diplomatic maneuvering is the reporting of Ian Fleming (creator of James Bond), who was in Istanbul as a correspondent for the London Sunday Times. Fleming deliberately used the term "riot" to emphasize spontaneity, contradicting numerous other accounts of an organized attack. Later, in his 1957 novel From Russia with Love, Fleming fully adopted the official Turkish and American narrative: that Soviet-backed communists instigated the violence.

This "communist myth" conveniently served the interests of both the Turkish and British governments. It deflected blame from the Menderes administration for its domestic troubles and helped Britain avoid UN intervention in its struggle to maintain control over Cyprus. The narrative was publicly endorsed by CIA Director Allen Dulles (who was also in Istanbul at the time) and Prime Minister Menderes, despite the near-total suppression of communism in Turkey at the time.

A Grim Testament

Photo: Lifo

The 1955 Istanbul Pogrom stands as a grim testament to how geopolitical disputes can be cynically manipulated to justify state-sponsored terror and ethnic cleansing. It was not a spontaneous riot but a calculated act of violence, directly linked to the Cyprus issue and designed to accelerate the "Turkification" of Turkish society by forcibly expelling its non-Muslim minorities. The active complicity of government agencies, the deliberate incitement by state-controlled media, and the criminal inaction of security forces reveal a dark chapter of state-sponsored terrorism.

Photo: Reader

The pogrom triggered a massive wave of emigration that decimated Istanbul's vibrant, centuries-old Greek community, reducing a population of over 65,000 in 1955 to a mere fraction of that number today. Its destructive impact created a legacy of deep-seated mistrust that continues to shape the complex and often fraught dynamics of Greco-Turkish relations. More than just a historical event, the pogrom of 1955 serves as a critical and painful lens through which we can understand the enduring challenges of nationalism, minority rights, and historical memory in the region.